- Home

- Andrea Thalasinos

Fly by Night Page 2

Fly by Night Read online

Page 2

Sitting down at her desk, Amelia lifted the glass jar containing Tyrian purple snail shells gathered by her father from the seashore in Crete. She slowly turned the jar, watching as the shells changed configurations and clinked together, tiny grains of sand still stuck inside the glass. Studying the lavender-white ridges and spikes of their exoskeletal bodies, she remembered the feel of being a young woman, yearning and wanting everything though not knowing what everything is.

She set the jar down and sighed. Facing the darkened computer screen, her face was the image of her mother’s. Pretty, though tired and puffy in the same places, prominent cheekbones, hollow cheeks, and jowls ever so slightly beginning to loosen as her mother’s might have at this age.

“Screw it,” she muttered and hit the keyboard, vowing to open the NSF e-mail if it was there. Then play along with Bryce and Jen or else fake them out by marinating her eyeballs with saline to look as though she’d been crying.

But her stomach squeezed as the screen lit up.

“What?”

A second e-mail from her late father—her spine straightened as if independent from the rest of her body.

She opened it. “Sorry to trouble you again, if you’d rather phone, I am in Wisconsin. Please call immediately…”

Immediately? What was so immediate about a man dead more than three decades? Was this a joke? A hacker parlaying a scam off NSF e-mail addresses?

She closed the e-mail and looked away. Staring past the tanks and out the back doors to Narragansett Bay, something felt wrong.

“Jesus,” she said, distracted from the NSF decision. She rested her elbows on the desk, leaning her chin in her palm.

“Amelia?”

She looked up.

“You okay?” It was the krill scientist from the other side of the bench.

“Uh—yeah.”

“Your people said to tell you they’re down at the AA,” he said in his soft voice.

“Thanks.” She always mirrored the man’s posture, hunching over a bit like him and speaking quietly.

The Ale Asylum, or AA, was a former psychiatric hospital circa 1920s turned brewery within walking distance of the university campus.

Just then her phone buzzed.

“Where are you?” Bryce texted.

“Where are YOU?” she shot back.

“AA. Pitchers and pizza! Waiting…”

“Leaving now,” she typed and was about to get up when Amelia turned to face the adjacent saltwater aquarium. It didn’t take long to get lost in the lush corals that undulated in the wake of the water filtration system; such beauty was always a surprise. “Geek TV” Bryce called it. The soft din of the motors was soothing. She’d bred and transported countless pairs of sea horses to the overfished areas in Indonesia, Malaysia, and many other parts of the world as well as to the New York Aquarium, Chicago’s Shedd. Sea horses were the proverbial canary in the coal mine, portending the health of ocean shorelines.

She tapped on the glass. A pair of bright yellow sea horses paused in their love dance to look up. They swam to her pressed finger.

“Hi, guys.” She leaned her forehead against the glass; its warmth from the aquarium lights felt safe, like she was all tucked in for the night and the world would never end. Their eyes moved independently as if deep in thought, dorsal and pectoral fins propelling them like hummingbird wings. They flitted away, resuming their intermingling and caressing of tails, once again more absorbed in courtship than fate—what it must be like to be so lost yet found.

Stuffing her phone into her pocket, she grabbed her jacket and bag and then dashed out the back doors toward the parking lot and her Jeep.

* * *

The music at the AA boomed in her chest wall. The host was about to shout a question when Amelia pointed toward the rear of the building where they always sat. The chairs were made of iron to discourage bar fights. “Had ‘em made special,” the owner had once told Jen. “By the time you pick up one of those suckers you’re too tuckered to do any real damage.”

She spotted Bryce towering against the back wall, slowly waving the NSF letter like a surrender flag to catch her attention. Jen was almost as tall and stood alongside Bryce with her glass raised.

Amelia counted heads. Thank God no Myles. Relieved yet disappointed, she shook it off, spotting a pitcher of half-drunk beer, a partially eaten pizza, and an empty chair for her.

Amelia stopped just shy of the table and swiped the letter out of Bryce’s fist before he had time to react.

She held it up in victory. Jen’s sequin bag sparkled in flashes under the house lights from where it sat on the table. Bryce always teased that it more resembled a Las Vegas sign than a purse.

Jen and Bryce began play fighting, trying to grab the letter back.

Nervous laughter blurted out as Amelia then stuffed it in her bra. They’d been excited to the point of being giddy since the Ocean Explorer’s discovery a month ago.

“Now don’t make me have to go in there and get it,” Bryce called over the music, hands on his hips.

“It’s Bryce’s turn,” Jen said loudly in that big sister way she had.

“Yes, it is.” Amelia turned and looked at him through soft eyes. She pulled out the envelope and handed it over, a lump forming in her throat. Every five years, they took turns opening the NSF grant notification.

Bryce then ripped open the envelope with his teeth in a hungry, pirate way, pretending to chew and swallow part of the paper flap.

“Ew—you’re sick,” Jen shouted over the music.

Yanking out the letter he then shot them both a goofy face before reading.

As he scanned, Amelia noticed his eyes stop. They drooped at the corners in such a way that she knew. Dive partners knew each other better than their spouses and their own dogs knew them. In emergencies they’d share dwindling air reserves with the commitment to surface together or not at all.

“No,” Amelia said quietly and sat down. It was like thirty-four years ago when the embassy phone call from Greece had come in to the dorm about her parents.

Bryce closed his eyes and passed the letter as he sat.

“Thank you for your application,” she read, “… however … given … we regret…” She stopped. The connecting ribs in her sternum felt like an assortment of mismatched bones that cracked as she took a breath.

She handed the letter to Jen.

“No way,” Jen mouthed, shaking her head as she too sat down to read. Then she closed her eyes, hunched over, and leaned toward Amelia, resting her head in Amelia’s lap like an eight-year-old.

Amelia touched the side of Jen’s blond hair.

“I’m sorry,” Amelia said.

The three of them sat lifeless, like a scene spliced into the wrong movie. Surrounded by gyrating crowds bursting with energy, people sang along with the deafening music.

An odd internal quiet lingered, one that often settles before the magnitude of something’s about to hit. Like when a tide draws out, far out, exposing rocks, starfish, and shipwrecks as curious beachcombers stand in wonderment, sometimes following the quiet, puzzled by the ocean’s strange behavior just before they spot a giant water wall blocking the horizon. As if nature’s giving you the chance to rally and garner whatever strength you might need before an onslaught. Like when at nineteen years old Amelia had hung up the pay phone without speaking and chose to raise her son, Alex, alone. Just like then, there was hollowness where feelings should be. What a plucky girl she’d been—plucky yet so afraid of everything.

“I’m sorry,” Amelia repeated, not knowing what else to say. “So, so sorry,” she said to Bryce, smoothing Jen’s hair like she had for Alex after he’d been roughed up on the middle-school bus.

In the early years she’d rehearse what to say in the event of getting turned down. Now she felt like she needed a twenty-pound dive belt just to stay seated.

“Let’s get out of here,” Amelia said as Jen sat up.

As they staggered out into the

chilly night air, Amelia clutched her jacket around her ribs. She thought to invite them back to the Revolution House but instead had to sit. Easing down at the nearest bistro table and chair secured to the building with long cables and padlocks, she felt nothing.

Surface frost on the tabletop glittered in the parking lot lights like a crazy princess’s eyes.

Bryce said. “You okay?”

“’Course not.”

The three of them were quiet before she spoke. “I just need to sit here a while, Bryce, that’s all. Let’s talk tomorrow—you two go on home.”

She rested her face in her hands.

2

Ted Drakos Jr., or TJ, was glad his mother had died before knowing the outcome of the vote.

“I know you’ll stop it, Ma’iingan Ninde,” his mother, Gloria, had said earlier that morning, just hours before she’d passed.

“Feel it in my bones.” She’d hugged her sides and exaggerated like an excited girl. Aside from a three-year stint in Germany as a Navy flight nurse where she’d met and married TJ’s father, Gloria had lived all her life on or near the Red Cliff Ojibwe Reservation. With short gray hair and thick glasses, his mother was still a beautiful woman at eighty-six. Dimples in her cheeks had showed even when not smiling—“Laughing Eyes” they’d called her.

“Appreciate the vote of confidence, Ma,” he’d said, though he knew such confidence was misplaced. Long ago she’d named him Wolf Heart, or Ma’iingan Ninde, in an Ojibwe ceremony: a heart that loves with fierce loyalty—quiet, ever watchful, but never calling attention unless required.

“’Cause I know you will,” she’d shot back.

But the sixty-one-year-old wolf biologist didn’t smile, wouldn’t indulge false hope. Life and death were an everyday part of his job and TJ knew full well the influence of the trophy-hunting, gun, and sporting lobbies working hand in hand with Wisconsin’s new political regime to remove the protected status of the state’s wolf population from the Endangered Species List.

He’d been headed down to Madison to testify before the state legislature against Act 169, the reinstatement of the wolf hunt. Despite hearing from a “friendly” senator that the bill already had enough votes to pass, heartsickness and rage compelled him to go in spite of it. He’d make them listen to his testimony so that no one could claim that “they hadn’t known.…” When he was through they’d all understand the consequences of their vote. He’d expose and make public their rejection of more than thirty years’ worth of scientific field data in favor of cronyism. His executive summary, as well as those of other biologists, had documented how reinstating a wolf hunt was both unjustifiable as well as potentially devastating to wolf families. With this knowledge, he thought, let them turn a deaf ear away from science and to instead embrace the bloodthirsty ways of their culture.

“You’d better leave now.” Gloria had looked over at the wall clock. “Or you’ll be late.”

TJ had stood in his navy blue suit that was tight at the waist and already uncomfortable. Car keys jingling in his hand, he was just about to head out but something felt off.

He glanced around, feeling like he was forgetting something, and brushed back the same wisp of gray hair that never seemed to grow long enough to be rubber-banded at the nape of his neck along with the rest.

“Ma’iingan Ninde, you see with their eyes,” Gloria said and smiled with an expression he couldn’t read. Since he was a little boy, she’d always said that the yellow green of his eyes were the eyes of a wolf.

As young as six, TJ would sit on fallen tree trunks in the woods, quiet for hours as he waited for wolves to find him. Once they did, he’d study the micro-expressions of their muzzles and cheeks, the tilt of their eyes. By ten he’d trained his eye to spot them through the feathery cover of leaves as he’d catch their eye. Talking back using his eyes, he’d believed they’d understood. And when the prairie grasses were damp he’d catch the sweet nuttiness of their scent just moments after they’d scampered off into the forest.

Wolves had always been synonymous with his mother. Often one or two would step out, sitting just far enough away to watch her hanging laundry as TJ helped. Sometimes a yearling or two, always with an adult, would lie down in the clearing near their house to sun. On pillows of tall field grass they’d roll around on their backs, pawing at each other’s mouths, teeth clicking as they’d play, baking in the sun until beginning to pant, at which time they’d jump up and saunter off into the coolness of the trees.

“You gonna be okay, Ma?” TJ raised his voice and picked up the cordless phone, setting it down next to her on the side table. “I’m calling every thirty minutes until Charlotte gets home so you better pick up.”

“But you know I hate those darn salespeople—”

“Pick up anyway or I’m calling Delbert,” TJ threatened. Being a nurse, his mother was funny about the 911 Tribal Emergency Ambulance showing up at their place.

Then a shade passed across his mother’s face.

TJ pulled back and blinked several times, wondering if it was just dry, scratchy eyes. But he’d seen what he’d seen.

His stomach sank, arms became slack with dread. Closing his eyes for an instant he must have seen wrong. This was his mother.

Only once before had he seen a shade—six years earlier when Long-Tooth, or B-1, one of the oldest wolves in the Sand River Wolf Pack, had died. For fifteen years TJ had followed the pack, including Long-Tooth, collecting data and detailed field notes about the oldest pack on the Bayfield Peninsula.

At the time, TJ had been returning e-mails in his garage/office in Red Cliff when struck with the sudden urge to stand. It was the kind of restlessness when something’s about to happen.

“Huh.” He’d pinched his bottom lip as he’d stood and walked to the center of the room. Turning around once, hand in his pocket, he’d wondered if maybe Charlotte, his wife, had called from the back porch.

Sliding open the door, he stepped out to listen. Just the usual woodland sounds. It was mid-September, about the same time of year, early morning and chilly.

TJ had glanced around, wondering what the hell he was doing until he’d spotted Long-Tooth standing at the edge of the woods, eyes on him. He’d then stepped out without a coat.

Turning to face the wolf, they’d watched each other’s eyes. The animal’s brow relaxed. A wide toothy grin greeted an old friend who’d been out of touch for some time.

The wolf was three-legged lame and limped into the tall field grass near the office and then stopped. Keeping a watchful eye on TJ, he turned in stiff, uncomfortable circles until finding the right spot. He then let out a sigh tinged with a groan before easing down onto the grass.

He hadn’t seen Long-Tooth that past spring and had wondered if the old guy hadn’t made it. Many of the old ones and yearlings hadn’t. It was startling how much older and thinner the wolf looked. Ratty coat, tail as bald as a possum’s where formerly it had been bushy and one of the most luxuriant TJ had seen when the animal would hold it high, asserting his place in the pack.

For as many springs as TJ could recall, Long-Tooth would spot him and Jimmy, his colleague, coming to perform the annual health checks. The wolf would make the pretense of running away before half jokingly turning to TJ as if to say, “Okay, go ahead, do it.”

TJ would then dart him and stand by as the tranquilizer took effect, watching as the wolf relaxed onto the ground, quickly wadding up his jacket to tuck underneath and cushion the animal’s head. He and Jimmy would then examine the animal’s teeth and gums, the insides of his ears, test the flexibility of his joints and then draw the required tubes of blood.

Then the two men would slip a sling under the animal, lifting him to get an annual weight after which they’d sit with him until fully awake again so as to not leave him defenseless.

Sometimes Long-Tooth would spot TJ and play “catch me.” The wolf would run ahead and then stop, looking back to ensure that TJ was following. Then he’d lead TJ up and down t

he steep ravines along Lake Superior to their den in the Chequamegon to show off his litter of four week-old pups.

This time Long-Tooth had rolled onto his side, tired from the effort it had taken to summon him. TJ sat cross-legged on the dewy grass in silence, vowing to stay with the wolf until either he got up or didn’t. He was used to waiting hours, days, sometimes weeks—that was what wildlife biologists did.

Juvenile eagles had soared above, their dark brown feathers the color of tree bark, playing and chasing each other from the top of one dead white pine to another. Once the sun was fully up, Long-Tooth lay peacefully; his eyes giving a chatoyant flash of cataracts.

Gravel sounds of Gloria pulling into the driveway made them both turn. She’d just moved in after turning eighty although still volunteering at the Red Cliff Health Center to give diabetes screenings to tribal members.

TJ timed how long it would take for Gloria to get inside and then phoned.

The wolf’s eyes then shifted onto Gloria as she negotiated the uneven ground toward them, a blanket bundled under each arm. Long-Tooth’s face moved with small jerky turns of his head as he watched with interest.

“He called you.” She said, out of breath as she reached them both, handing TJ a blanket.

“Yeah.”

Gloria eased down to sit with the same stiffness as the wolf.

She wasn’t one for the magic talk but then again neither was he.

“He doesn’t want to be alone,” she said.

TJ nodded, his head dropped.

“You’ve been a good friend.” She touched her son’s knee.

TJ choked up.

“He knows you’re sad, Ma’iingan Ninde.”

As she squeezed his knee TJ felt her studying his profile. His father’s nose, she’d always say, only this time she hadn’t. Her voice was soft, as if he was ten years old.

“But he’s glad you came. They don’t see death like we do.”

They’d sat in silence for a while.

“He just wants company,” she said.

TJ nodded.

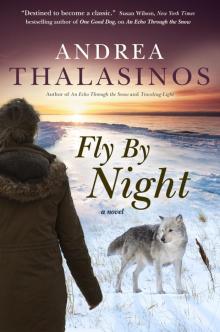

Fly by Night

Fly by Night